#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

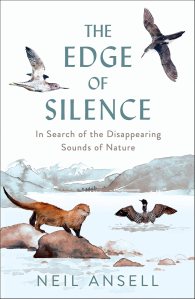

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Weatherglass Novella Prize 2026

Following up on the shortlist news I shared in November: Ali Smith has chosen two winners for the second annual Weatherglass Novella Prize. Both of these have changed title since they were submitted as manuscripts (From the Smallest Things to The Hyena’s Daughter; Shougani to Pink Soap). I’m particularly interested in Jones’s novel about Mary Shelley and her sister and stepsister. And the Gaston has a brilliant cover!

Here’s what Ali Smith had to say about the winning books, courtesy of the Weatherglass Substack:

The Hyena’s Daughter by Jupiter Jones

(to be published in April 2026)

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“This novella tells the far-too-untold story of a c19th sisterhood, that of the daughters of Mary Wollstonecraft: Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, the famed writer of Frankenstein, plus their step[-]sister Claire Clairmont. Are they the three graces? The fates? They’re women, as alive and breathing and rebellious and analytical as you and me, and well aware and critical of the hemmed-in nature they’re expected to accept as women of their time, a time of ‘a new way of thinking, a new-world independence, a revolutionary world.’

“It features their connection to Percy Bysshe Shelley – ‘how could we not love him, with his lofty ethics and words that flew like birds?’ – and many of the other contemporary poets and thinkers of the time. Pacy and assured, it turns its history to life from fragment to sensuous fragment. If the dead brought to life is to be Mary Shelley’s theme, this novella asks what the real source of life spirit is, the vital spark. This novella, full of detail and richesse, is a piece of vitality in itself.”

Pink Soap by Anju Gaston

(to be published in June 2026)

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“‘I ask the internet the difference between something being too close to the bone and something being too close to home.’ This funny and terrifying book is a study of what and how things mean, and don’t, in our latest machine age. In it something unforgivable has happened. The main character in this novella, seemingly numbed but bristling with blade-sharp understanding, is only just holding things together and trying to work out how to heal. So she travels to Japan in a search for the other half of a fragmented family. Or is it the world itself that has fragmented?

“Pink Soap examines the massive everyday pressures we’re all under with real wit and style. It is pristine, brilliant, smart beyond belief. I sense it becoming as much a classic for now as Plath’s The Bell Jar has been for the decades behind us.”

Submissions have already opened for the 2027 Prize. More information is here.

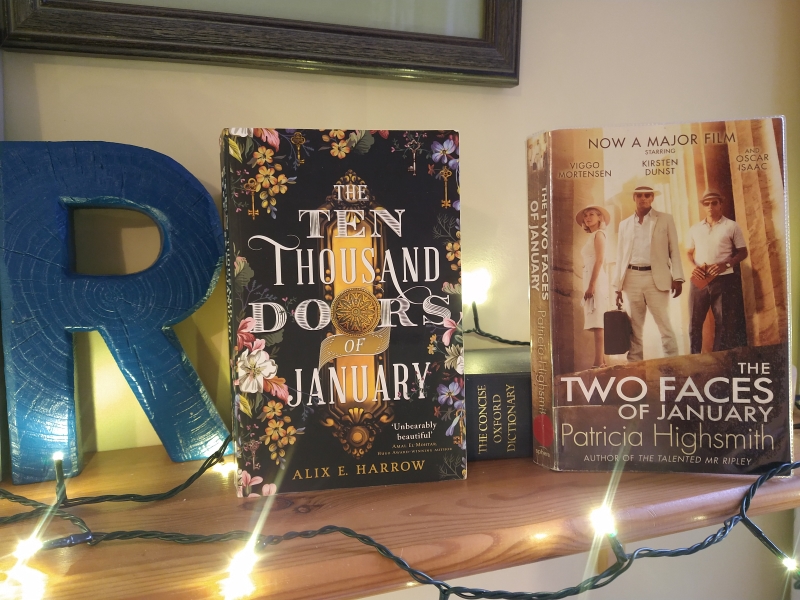

January Novels by Alix E. Harrow & Patricia Highsmith

The month of January was named for the Roman god Janus, known for having two faces: one looking backward, the other forward. “He presided not over one particular domain but over the places between – past and present, here and there, endings and beginnings,” as Alix E. Harrow writes. In her novel, the door is a prevailing metaphor for liminal times and spaces; Highsmith’s work, too, focuses on the way life often pivots on tiny accidents or decisions.

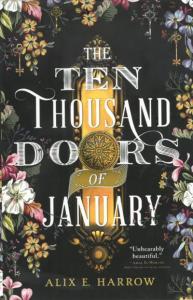

The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow (2019)

“I didn’t want to be safe … I wanted to be dangerous, to find my own power and write it on the world.”

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

As the mixed-race ward of a wealthy collector, January Scaller grows up in a Vermont mansion with a dual sense of privilege and loss. She barely sees her brown-skinned father, who travels the world amassing treasures for Mr. Locke and his archaeological society; and her mother’s absence is an unexplained heartbreak. But when her father also disappears in 1911 – to be apparently replaced by an African governess named Jane Irimu (it’s her quote above) and an enticing scholarly manuscript entitled The Ten Thousand Doors – 17-year-old January discovers the power of words to literally open doors to new worlds, and sets off on a quest to reunite her family. At every turn, though, she’s thwarted by evil white men who, after plundering foreign cultures, intend to close the doors of opportunity behind them.

This was an unlikely book for me to pick up: I didn’t get on with that whole wave of books with books and keys on the cover (Bridget Collins et al.) and wouldn’t willingly pick up romantasy – yet this features two meant-to-be romances fought for across worlds and eras. I grow impatient with a book-within-the-book format. But The Chronicles of Narnia, which no doubt inspired Harrow, were my favourite books as a child. Especially early on, I found this as thrilling as The Absolute Book and The End of Mr. Y. Whereas those doorstoppers held my interest all the way through, though, this became a trudge at a certain point. Harrow is maybe a little too pleased with her own imagination and turns of phrase, like T. Kingfisher. (Bad the dog is also in peril far too often.) In the end, this reminded me most of Babel by R.F. Kuang with its postcolonial conscience and words as power. I enjoyed this enough that I think I’ll propose her The Once and Future Witches for book club. (Little Free Library) ![]()

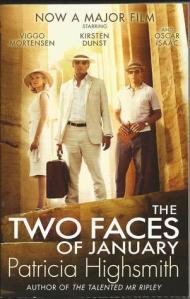

The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith (1964)

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

Three American vacationers meet in a hotel in Greece one January. But the circumstances are far from auspicious. Conman Chester MacFarland is traveling with his 15-years-younger wife, Colette. Rydal Keener is a stranger who, seemingly on a whim, helps them cover up the accidental death of a Greek police investigator who came to ask Chester some questions. From here on in, they’re in lockstep, moving around Greece together, obtaining fake passports and checking the headlines obsessively to outrun consequences. Colette takes a fancy to Rydal, and the jealousy emanating from the love triangle is complicated by Chester’s alcoholism and Rydal’s hurt over earning a police record for a consensual teenage relationship. I have a dim memory of seeing the 2014 Kirsten Dunst and Viggo Mortensen film, but luckily I didn’t recall any major events. A climactic scene takes place at the palace of Knossos, and the chase continues until an unavoidably tragic end.

I’ve read several Ripley novels and a few standalone psychological mysteries by Highsmith and enjoyed them well enough, but murders aren’t really my thing. (Carol is the only work of hers that I’ve truly loved.) My specific issue here was with the central trio of characters. Colette is thinly drawn and doesn’t get enough time on the page. Chester seems much older than his 42 years and is an irredeemable swindler. It’s only because of our fondness for Rydal that we want them all to get away with it. But even Rydal doesn’t get the in-depth portrayal one might hope for. There’s the injustice of his backstory and the fact that he’s a would-be poet, true, but we never understand why he helped the MacFarlands, so have to conclude that it was the impulse of a moment and committed him to a regrettable course. This is pacey enough to keep the pages turning, but won’t stick with me. (Public library) ![]()

I’m turning my face forward: Good riddance to January 2026, during which I’ve mostly felt rubbish; here’s hoping for a better rest of the year. I’m off to the opera tonight – something I’ve only done once before, in Leeds in 2006! – to see Susannah, a tale from the Apocrypha transplanted to the 1950s U.S. South.

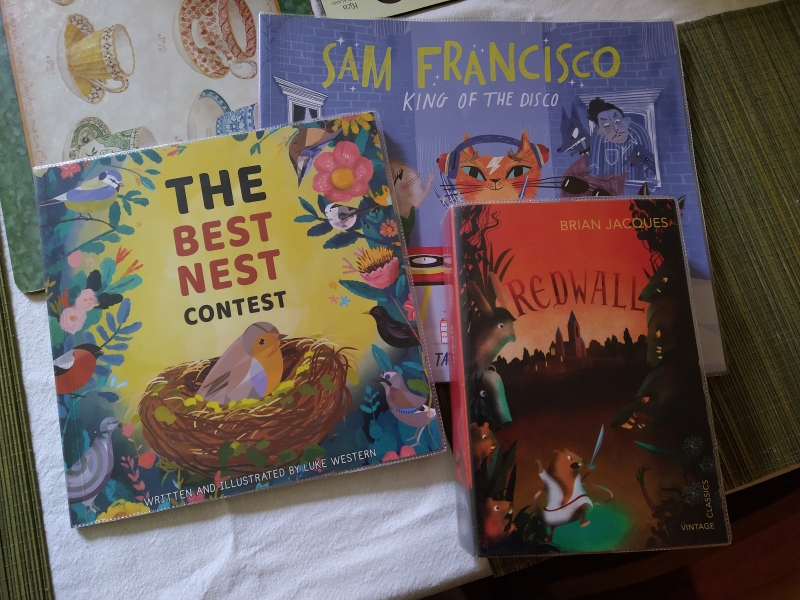

Love Your Library: January 2026

Thanks to Eleanor, Laura and Skai for posting about their recent reading from the library! Margaret has also contributed a profile of a library she visited in Spain.

It’s been a lighter library month for me because I’ve been focusing on my own shelves. You can tell I’ve been looking for comfort reads during a damp, dark and illness-marred month, as there have been a lot of children’s books on my stacks, including Redwall, part of a series I loved when I was a kid. Rereading it 33 years or so later, it’s hard to recapture the magic, but I’m enjoying it well enough.

This Independent subheading was served up to me on Facebook early in the month: “Library use in the UK is dwindling with less than a third of the population using a library service in the last year.” To me, that’s a sad and shocking statistic. A staff member at the library where I volunteer said that loans are down at the moment and it’s important to increase them. Well, I’m doing my best (see reservation list below)!

My library use over the last month:

READ

- The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith

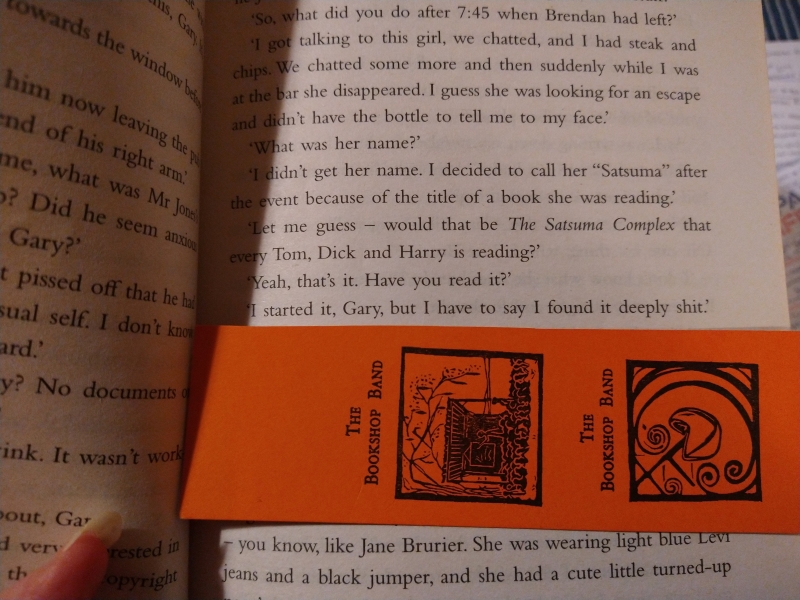

- The Satsuma Complex by Bob Mortimer

An attempt at a meta passage reveals the stark truth about this one!

- Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens

- Sam Francisco, King of the Disco by Sarah Tagholm, illus. Binny Talib

- The Best Nest Contest by Luke Western

SKIMMED

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

CURRENTLY READING

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

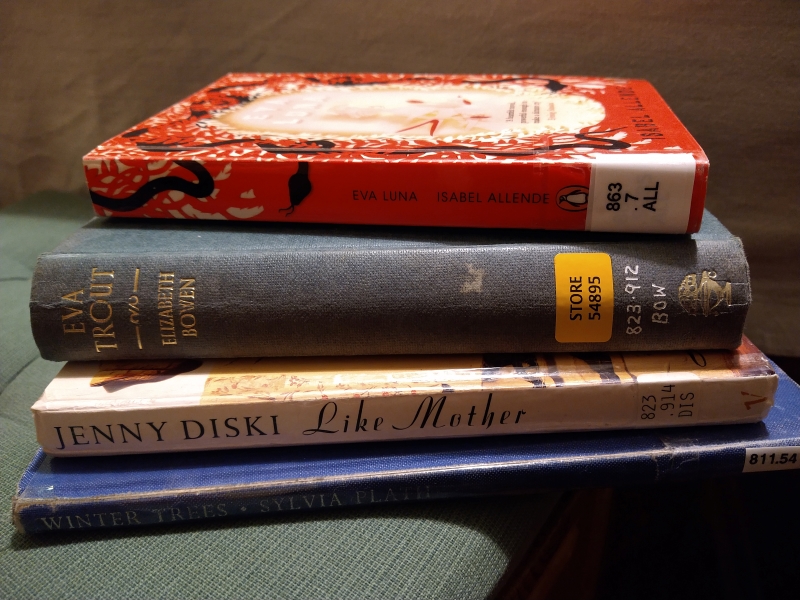

- Eva Trout by Elizabeth Bowen (for February book club – classics subgroup)

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Redwall by Brian Jacques (reread)

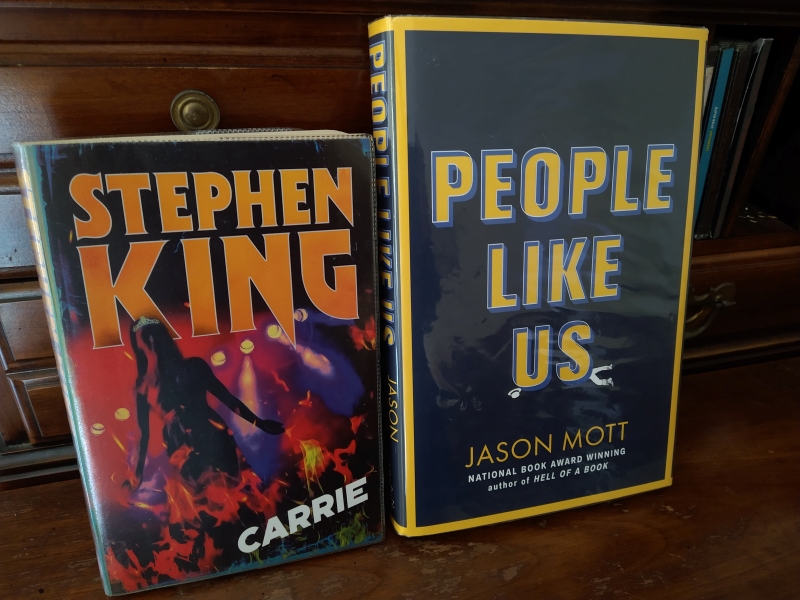

- Carrie by Stephen King

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

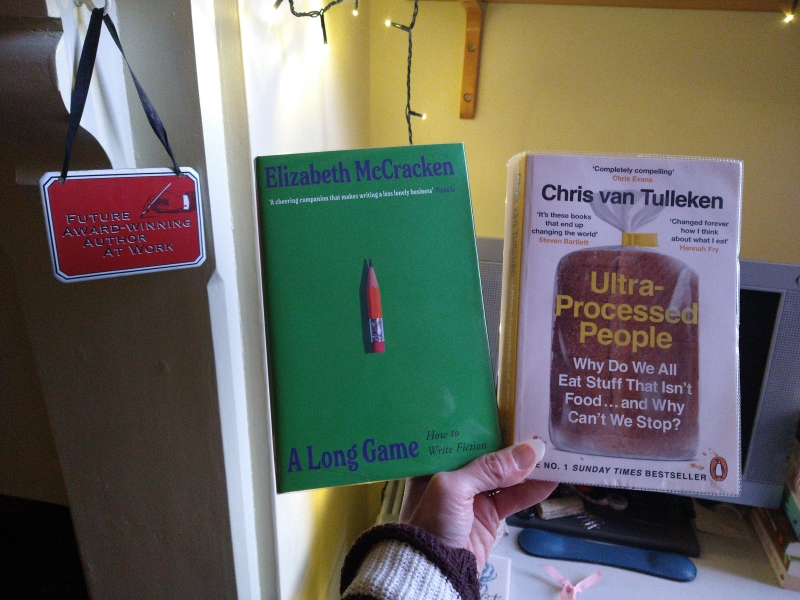

- A Long Game: How to Write Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken

- People Like Us by Jason Mott

- Ultra-Processed People: Why Do We All Eat Stuff that Isn’t Food … and Why Can’t We Stop? by Chris van Tulleken (for February book club)

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

A rare university library book haul…

- Eva Luna by Isabel Allende (for April book club)

- Like Mother by Jenny Diski

- Winter Trees by Sylvia Plath

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Strangers: The Story of a Marriage by Belle Burden

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- The Swell by Kat Gordon

- Leaving Home: A Memoir in Full Colour by Mark Haddon

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- The Brain at Rest: Why Doing Nothing Can Change Your Life by Joseph Jebelli

- Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy

- Skylark by Paula McLain

- Frostlines: An Epic Exploration of the Transforming Arctic by Neil Shea

- First Class Murder by Robin Stevens

- Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward

Also … I took a cue from Eleanor and, even though I felt a little sheepish about it, sent an e-mail to the stock librarian back in November asking if the library system could acquire certain books for me. I thought maybe they’d purchase a few of my requests, but they bought all 13! So I’ve placed holds on all but one (I’ll wait until summer to borrow and read Kakigori Summer by Emily Itami). I hope other patrons will get much enjoyment out of these, too!

Fiction:

-

- I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman

- The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley

- Bog Queen by Anna North

- Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange

- Carrion Crow by Heather Parry

- Let the Bad Times Roll by Alice Slater

- The Original by Nell Stevens

- Pick a Colour by Souvankham Thammavongsa

- The First Day of Spring by Nancy Tucker

Nonfiction:

-

- Pathfinding by Kerri Andrews

- Everything Is Tuberculosis by John Green

- The Spirituality Gap by Abi Millar

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- We Live Here Now by C.D. Rose – Requested off of me, but I’ll get it back out another time.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

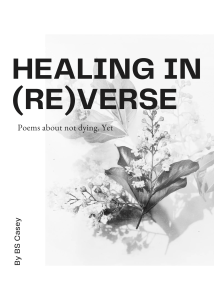

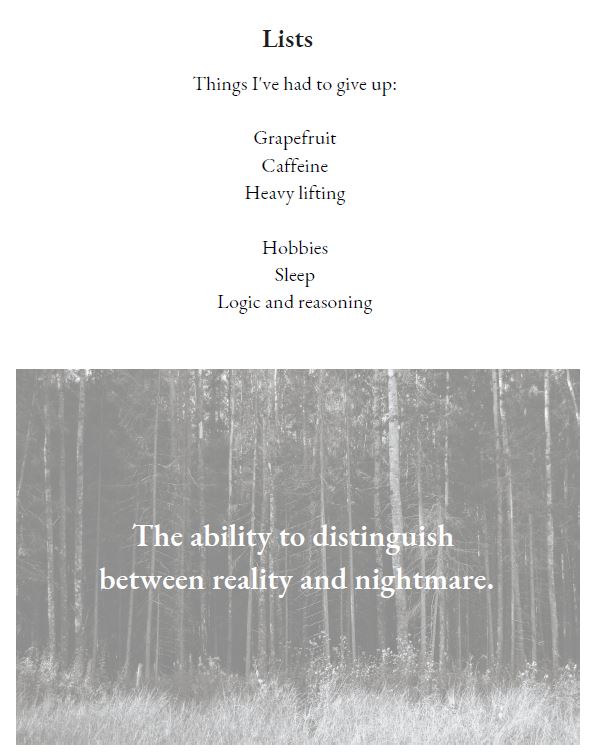

Healing in (Re)Verse: Poems about not dying. Yet by BS Casey (Blog Tour)

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

Bee Casey’s self-published debut collection contains a hard-hitting set of accessible poems arising from the conjunction of mental health crisis and disability. It opens with the sense of a golden era never to be regained: “the girl before / commanded the room // Oh how I wish I could even walk into it now.” Now the body brings only “pain and cruelty”: “an unwelcome guest / lingers on my chest / in bones and my home”.

End rhymes, slant rhymes, and alliteration form part of the sonic palette. Through imagined conversations with the self and with others who have hurt the speaker or put them down, they wrestle with concepts of forgiveness and self-love. “Just a girl” chronicles instances of sexualized verbal and emotional abuse. The use of repeated words and phrases, with minor adaptations, along with the themes of trauma and recovery, reminded me of Rupi Kaur’s performance poetry-inspired style. “Monster” is more like a short story with its prose paragraphs and imagined dialogue. “How are you” is an erasure poem that crosses out all the possible genuine answers to that question in between, leaving only the socially acceptable “I’m fine thanks. … how are you?”

The pages’ stark black-and-white design is softened by background images of flowers, feathers, forests, candle flames, and shadows falling through windows. Although the tone is overwhelmingly sad, there is also some wry humour, as in the below.

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Casey has only just turned 30, and it’s sobering to think how much they’ve gone through in that short time and how often suicide has been a temptation. It’s a relief to see that their view of life has shifted from it being a trial to a gift. “What an honour, a privilege / What beauty to grow old.” Sometimes for them, not dying has to be an active decision, as in the poem “Tomorrow I will kill myself,” but the habit can stick – for 15 years “I’ve been too busy / Accidentally being alive.”

Poetry – writing it or reading it – can be a great way for people to work through the pain of mental ill health and chronic illness and not feel so alone. That’s one reason I’m looking forward to the return of the Barbellion Prize later this year. “The Barbellion Prize celebrates and promotes writing that represents the experience of chronic illness and disability. The prize is named after the diarist W.N.P. Barbellion, who wrote eloquently on his life with multiple sclerosis (MS). It is a cross-genre award for literature published in the English language.” I’ve donated to get it up and running again; maybe you can, too?

My thanks to Random Things Tours and the author for the advanced e-copy for review.

See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

The 2026 Releases I’ve Read So Far

I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid reviews for Foreword and Shelf Awareness. (I already previewed six upcoming novellas here.) Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet, so I’ll just give brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest. I link to the few that have been published already, then list the 2026 books I’m currently reading. Soon I’ll follow up with a list of my Most Anticipated titles.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood.

Simple Heart by Cho Haejin (trans. from Korean by Jamie Chang) [Other Press, Feb. 3]: A transnational adoptee returns to Korea to investigate her roots through a documentary film. A poignant novel that explores questions of abandonment and belonging through stories of motherhood. ![]()

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The Conspiracists: Women, Extremism, and the Lure of Belonging by Noelle Cook [Broadleaf Books, Jan. 6]: An in-depth, empathetic study of “conspirituality” (a philosophy that blends conspiracy theories and New Age beliefs), filtered through the outlook of two women involved in storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021. ![]()

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans.

The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman [Counterpoint, Feb. 24]: The staff members of a fine-dining restaurant each have a moment in the spotlight during the investigation of a theft. Linked short stories depict character interactions and backstories with aplomb. Big-hearted; for J. Ryan Stradal fans. ![]()

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye.

Taking Flight by Kashmira Sheth (illus. Nicolo Carozzi) [Dial Press, April 21]: A touching story of the journeys of three refugee children who might be from Tibet, Syria and Ukraine. The drawing style reminded me of Chris Van Allsburg’s. This left a tear in my eye. ![]()

Currently reading:

(Blurb excerpts from Goodreads; all are e-copies apart from Evensong)

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Visitations: Poems by Julia Alvarez [Knopf, April 7]: “Alvarez traces her life [via] memories of her childhood in the Dominican Republic … and the sisters who forged her, her move to America …, the search for mental health and beauty, redemption, and success.”

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Our Numbered Bones by Katya Balen [Canongate, 12 Feb. / HarperVia, Feb. 17]: Her “adult debut [is] about a grieving author who heads to rural England for a writer’s retreat, only to stumble upon an incredible historical find” – a bog body!

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Let’s Make Cocktails!: A Comic Book Cocktail Book by Sarah Becan [Ten Speed Press, April 7]: “With vivid, easy-to-follow graphics, Becan guides readers through basic techniques such as shaking, stirring, muddling, and more. With all recipes organized by spirit for easy access, readers will delight in the panelized step-by-step comic instructions.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Monsters in the Archives: My Year of Fear with Stephen King by Caroline Bicks [Hogarth/Hodder & Stoughton, April 21]: “A fascinating, first of its kind exploration of Stephen King and his … iconic early books, based on … research and interviews with King … conducted by the first scholar … given … access to his private archives.”

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico [Mad Creek Books, Feb. 17]: “Can a lesbian who loves a trans man still call herself a lesbian? As D’Amico tries to engage more deeply with the man she is married to, she looks at all the men—historical figures, politicians, men in her family—in search of clear dividing lines”.

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

See One, Do One, Teach One: The Art of Becoming a Doctor: A Graphic Memoir by Grace Farris [W. W. Norton & Company, March 24]: “In her graphic memoir debut, Grace looks back on her journey through medical school and residency.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

Nighthawks by Lisa Martin [University of Alberta Press, April 2]: “These poems parse aspects of human embodiment—emotion, relationship, mortality—and reflect on how to live through moments of intense personal and political upheaval.”

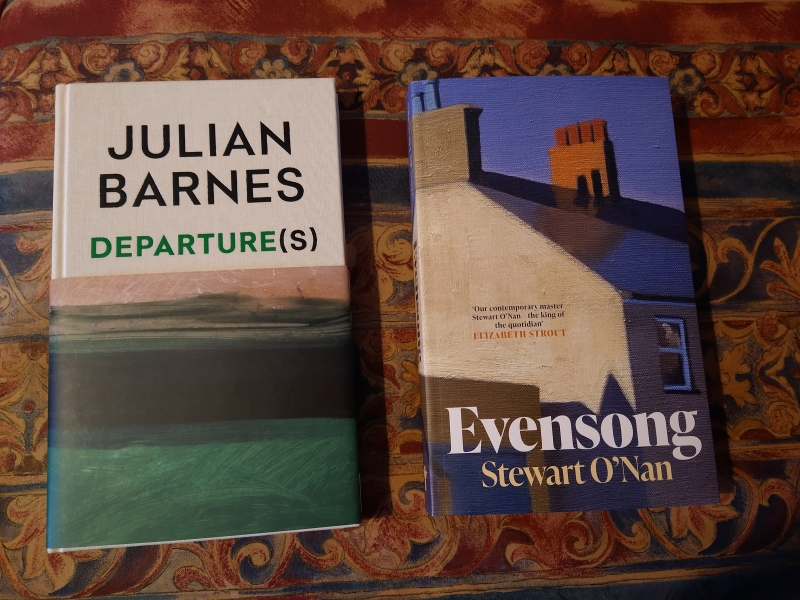

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan [published in USA in November 2025; Grove Press UK, 1 Jan.]: “An intimate, moving novel that follows The Humpty Dumpty Club, a group of women of a certain age who band together to help one another and their circle of friends in Pittsburgh.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

This Is the Door: The Body, Pain, and Faith by Darcey Steinke [HarperOne, Feb. 24]: “In chapters that trace the body—The Spine, The Heart, The Knees, and more—[Steinke] introduces sufferers to new and ancient understandings of pain through history, philosophy, religion, pop culture, and reported human experience.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

American Fantasy by Emma Straub [Riverhead, April 7 / Michael Joseph (Penguin), 14 May]: “When the American Fantasy cruise ship sets sail for a four-day themed voyage, aboard are all five members of a famous 1990s boyband, and three thousand screaming women who have worshipped them for thirty years.”

Additional pre-release review books on my shelf:

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Shooting Up by Jonathan Tepper [Constable, 19 Feb.]: “Born into a family of American missionaries driven by unwavering faith … Jonathan’s home became a sanctuary for society’s most broken … AIDS hit Spain a few years after it exploded in New York and, like an invisible plague, … claimed countless lives – including those … in the family rehabilitation centre.”

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Elizabeth and Ruth by Livi Michael [Salt Publishing, 9 Feb.]: “Based on the real correspondence between Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens … [Gaskell] visits a young Irish prostitute in Manchester’s New Bailey prison. … [A] story of hypocrisy and suppression, and how Elizabeth navigates the … prejudice of the day to help the young girl”.

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2026 reads you can recommend?

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in

I’ve found Bloom’s short stories more successful than her novels. This is something of a halfway house: linked short stories (one of which was previously published in  The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

The title story opens a collection steeped in the landscape and history of Orkney. Each month we check in with three characters: Jean, who lives with her ailing father at the pub they run; and her two very different suitors, pious Peter and drunken Thorfinn. When she gives birth in December, you have to page back to see that she had encounters with both men in March. Some are playful in this vein or resemble folk tales: a boy playing hooky from school, a distant cousin so hapless as to father three bairns in the same household, and a rundown of the grades of whisky available on the islands. Others with medieval time markers are overwhelmingly bleak, especially “Witch,” about a woman’s trial and execution – and one of two stories set out like a play for voices. I quite liked the flash fiction “The Seller of Silk Shirts,” about a young Sikh man who arrives on the islands, and “The Story of Jorfel Hayforks,” in which a Norwegian man sails to find the man who impregnated his sister and keeps losing a crewman at each stop through improbable accidents. This is an atmospheric book I would have liked to read on location, but few of the individual stories stand out. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)  Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with

Mantel is best remembered for the Wolf Hall trilogy, but her early work includes a number of concise, sharp novels about growing up in the north of England. Carmel McBain attends a Catholic school in Manchester in the 1960s before leaving to study law at the University of London in 1970. In lockstep with her are a couple of friends, including Karina, who is of indeterminate Eastern European extraction and whose tragic Holocaust family history, added to her enduring poverty, always made her an object of pity for Carmel’s mother. But Karina as depicted by Carmel is haughty, even manipulative, and over the years their relationship swings between care and competition. As university students they live on the same corridor and have diverging experiences of schoolwork, romance, and food. “Now, I would not want you to think that this is a story about anorexia,” Carmel says early on, and indeed, she presents her condition as more like forgetting to eat. But then you recall tiny moments from her past when teachers and her mother shamed her for eating, and it’s clear a seed was sown. Carmel and her friends also deal with the results of the new-ish free love era. This is dark but funny, too, with Carmel likening roast parsnips to “ogres’ penises.” Further proof, along with  Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s

Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop (2013): I loved Bishop’s  A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical

A Rough Guide to the Heart by Pam Houston (1999): A mix of personal essays and short travel pieces. The material about her dysfunctional early family life, her chaotic dating, and her thrill-seeking adventures in the wilderness is reminiscent of the highly autobiographical  The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier – A pleasant year’s diary of rural living and adjusting to her husband’s new diagnosis of neurodivergence.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume. Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year. Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher) Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order) Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted  Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download) Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download) Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer. The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.” Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download) Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.” Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”. John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download) Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download) Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download) The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download) Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.” It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download) Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.” Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)